A Personal Adventure in Science Communication

It's March of last year and I'm driving a rental car from Chicago to Minneapolis with a friend of mine who's been trying to force me to listen to NPR's Hidden Brain podcast for months on end. At this point, I'm somewhat weirdly all about late-Romantic Scandinavian composers, and probably arguing for listening to an Alfvén symphony, but I relent. The quiet parts always nestle silently under the ambient whirs and hums of driving anyway. A soothing voice emerges from the speakers.

It's September of last year and I've just bought my own car for my 45-minute commute each way to Stony Brook. It's a Honda Civic, which amuses me because it sounds like it could be a paper co-authored by two mathematicians who work in fields closely tied to my research interests. Despite my surprisingly non-millennial relationship with technology, I'm eager to get the music pumping to save me from the Nesconset Highway monotony. I pay for Spotify for a reason, after all. For a few weeks, I'm singing along with Sibelius and Tchaikovsky (ahh the joys of being alone in a car), or alternatively not singing along with Schoenberg. But it feels somewhat unfulfilling, and it hits me like a battering ram that I really have a hole in my heart, that I feel like I'm missing out on so much of the world, and that there's so much more I want to learn about. Probably while listening to Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 6, now that I think about it. I decide to fill the hole with Hidden Brain, which I proceed to listen to every single journey in my car for the next three weeks. It's bite-sized and easy-to-understand and well-produced and super-engaging and surprisingly nuanced. I highly recommend it.

Quick digression - a friend once told me that he thought that nobody should be allowed to clap after a performance of Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 6. They should just leave with the depressing finale embedded in their soul. The more I think about it, the more I'm inclined to agree.

Anyway, I started wondering whether I'd like natural sciences podcasts as much as Hidden Brain, which focuses on social science. I figured that maybe it's a lot harder to enjoy pop science when you're in the field itself. For example, I wonder if social scientists enjoy Malcolm Gladwell as much as the general population. When it's your own field, maybe there's a tendency to shout "oversimplification" from the frustrated peanut gallery. Then again, I thought, maybe that's not as much of a problem in my field, because mathematicians tend to have a religious dedication to precision. In fact, I'd long been familiar with the YouTube channel Numberphile, which has had some really fantastic videos and indeed rarely suffers from oversimplification.

As I pondered this question, and as my love affair with science communication was blossoming, the following subject line popped into my Stony Brook e-mail:

A clerical error had placed me in the position of a one-day decision - would I sign up for this competition I had never heard of before? Exclamation marks in e-mails frighten me a little bit, but I clicked on the link to the Postdoc Spotlight homepage regardless, and decided rather impulsively that of course I would signup! The next day, I mentioned my haphazard decision to a colleague of mine, explaining that I would have to try to break down my research to explain it to a general audience. "How long is the presentation?" he asked. "I don't know, an hour?" I replied. Obviously, I hadn't read the website thoroughly, and I only wish there was a picture of the horror on my face when I discovered later that day that my presentation would have to be a measly 5 minutes.

It had been a while since my middle and high school days of watching science programs on TV, so I thought it wise to surround myself with examples of effective science communication in preparation. Heading back down the podcast rabbit hole, I started listening to The Infinite Monkey Cage on my commutes. It's a completely different flavor of show from Hidden Brain, in that it comes with a comedic twist and doesn't evoke the ASMR that Shankar's voice does. But it's still fun, and has a surprising amount of insight for a relatively non-serious podcast. (More recently, I've been enjoying a few more podcasts on my commute, including The Joy of x and My Favorite Theorem... and also Coffee Break French but that's probably less relevant to this post.) As the weeks wore on, I had to turn my podcast-listening efforts into a successful presentation.

Maybe I'm alone in thinking this, but in mathematics, I sense some low-level animosity against slide talks, and heaven help you if your slides are anything but a Beamer presentation. So imagine the panic when, for our Postdoc Spotlight presentations, we were encouraged to use PowerPoint (*gasp*). It had been years since I had opened the devil's program, and I was honestly a bit scared, but in the end, I've come to the controversial opinion that PowerPoint is actually fantastic. Now, let me clarify. I'm not saying most PowerPoint presentations are fantastic - that certainly isn't the case. But actually, I found that it was extremely well suited to the type of talk I was giving: clear but fast-paced, with wordless slides. (I haven't yet tried out PowerPoint for a research presentation, but maybe one day soon I'll make the jump.)

PowerPoint aside, there were two things which were important to me in preparing my talk. The first was that it legitimately had to be about my own research, as opposed to being purely expository. The second was that I had to present it with a certain level of integrity. Of course I would have to sweep some details under the rug, but I really didn't want to misconstrue what I was doing. I realized pretty quickly that the story I wanted to tell had two major threads, and I struggled to figure out how to tie them together. Throughout the process, I felt like I could produce an amazing 15-minute presentation with both of these threads properly treated, but that the 5-minute version always felt like a two-headed monster. The word "impossible" was thrown around at some point when I mentioned to a colleague what I was attempting to do, and for a while, I really believed it was an impossible task. As I cut out slides, the story didn't feel as coherent. As I rearranged the slides, it seemed like there was no solution. In a really early draft, I even had a bunch of slides which were overtly philosophical, attempting to answer the dreaded question of why pure mathematics is useful at all. It legitimately wasn't until the final version that I felt like I had produced a cohesive and compact story which fit in the time constraints.

There were a number of things I learned from the process, and a lot of them can be phrased pretty generically (for example, distilling a message for a lay audience is actually helpful in understanding the big picture of one's own research). But I want to share a somewhat surprising one, which is that artistic direction is very important to me. I spent a lot of time designing my slides, and in the end, it's one of the aspects of my presentation that I'm most proud of. As a consequence, I've found myself really caring about artistry in my academic life, including not just the design of mathematical figures in lecture notes and research articles, but also the design of my website and this blog.

With all that out of the way, here is my presentation:

"This is Hidden Brain. I'm Shankar Vedantam."

What follows is an incredible story about two pairs of Colombian twins who were mixed up at birth, and I'm hooked. (Seriously, though, if you haven't heard about this, check it out.) I never thought of myself as a podcast person, but for the first time, I'm seduced by the riveting exploration of nature and nurture. We listen to a second episode of Hidden Brain before switching back to some easy-driving indie music (but not Beach House, to my friend's chagrin). It's the last time I listen to a podcast for a number of months.

From a young age, I've always been interested in how to communicate math to a general audience. I grew up watching Michio Kaku and Stephen Hawking and Brian Greene explain the mysteries of the cosmos on The Discovery Channel and The Science Channel and The History Channel (I never really understood why they would be on The History Channel, but no matter), and that sense of wonder I had as a kid stuck with me. But it was always physics on these TV programs, almost never pure math, and I've always been a interested in pushing for public mathematics to have a larger audience. Not that it doesn't exist (see later in the post), but in the pre-YouTube and pre-everyone-and-their-dog-has-a-blog renaissance, it was a lot less common, as far as I can tell.

So it's no surprise that in August of last year, when I saw an advertisement for a science communication workshop held through the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook, I signed up immediately. It was essentially a glorified improv workshop, and I absolutely adored every minute of it. Whereas throughout graduate school I had spent a lot of time figuring out the dinner party pitch, mostly by trial and error at dinner parties, I never really thought so much about the elevator pitch. Refining the open-ended explanations down to an engaging, convincing, and compact package was a rewarding and entertaining challenge.

From a young age, I've always been interested in how to communicate math to a general audience. I grew up watching Michio Kaku and Stephen Hawking and Brian Greene explain the mysteries of the cosmos on The Discovery Channel and The Science Channel and The History Channel (I never really understood why they would be on The History Channel, but no matter), and that sense of wonder I had as a kid stuck with me. But it was always physics on these TV programs, almost never pure math, and I've always been a interested in pushing for public mathematics to have a larger audience. Not that it doesn't exist (see later in the post), but in the pre-YouTube and pre-everyone-and-their-dog-has-a-blog renaissance, it was a lot less common, as far as I can tell.

So it's no surprise that in August of last year, when I saw an advertisement for a science communication workshop held through the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook, I signed up immediately. It was essentially a glorified improv workshop, and I absolutely adored every minute of it. Whereas throughout graduate school I had spent a lot of time figuring out the dinner party pitch, mostly by trial and error at dinner parties, I never really thought so much about the elevator pitch. Refining the open-ended explanations down to an engaging, convincing, and compact package was a rewarding and entertaining challenge.

It's September of last year and I've just bought my own car for my 45-minute commute each way to Stony Brook. It's a Honda Civic, which amuses me because it sounds like it could be a paper co-authored by two mathematicians who work in fields closely tied to my research interests. Despite my surprisingly non-millennial relationship with technology, I'm eager to get the music pumping to save me from the Nesconset Highway monotony. I pay for Spotify for a reason, after all. For a few weeks, I'm singing along with Sibelius and Tchaikovsky (ahh the joys of being alone in a car), or alternatively not singing along with Schoenberg. But it feels somewhat unfulfilling, and it hits me like a battering ram that I really have a hole in my heart, that I feel like I'm missing out on so much of the world, and that there's so much more I want to learn about. Probably while listening to Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 6, now that I think about it. I decide to fill the hole with Hidden Brain, which I proceed to listen to every single journey in my car for the next three weeks. It's bite-sized and easy-to-understand and well-produced and super-engaging and surprisingly nuanced. I highly recommend it.

Quick digression - a friend once told me that he thought that nobody should be allowed to clap after a performance of Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 6. They should just leave with the depressing finale embedded in their soul. The more I think about it, the more I'm inclined to agree.

Anyway, I started wondering whether I'd like natural sciences podcasts as much as Hidden Brain, which focuses on social science. I figured that maybe it's a lot harder to enjoy pop science when you're in the field itself. For example, I wonder if social scientists enjoy Malcolm Gladwell as much as the general population. When it's your own field, maybe there's a tendency to shout "oversimplification" from the frustrated peanut gallery. Then again, I thought, maybe that's not as much of a problem in my field, because mathematicians tend to have a religious dedication to precision. In fact, I'd long been familiar with the YouTube channel Numberphile, which has had some really fantastic videos and indeed rarely suffers from oversimplification.

As I pondered this question, and as my love affair with science communication was blossoming, the following subject line popped into my Stony Brook e-mail:

Fwd: Last chance to sign up to present your research at Postdoc Spotlight!

A clerical error had placed me in the position of a one-day decision - would I sign up for this competition I had never heard of before? Exclamation marks in e-mails frighten me a little bit, but I clicked on the link to the Postdoc Spotlight homepage regardless, and decided rather impulsively that of course I would signup! The next day, I mentioned my haphazard decision to a colleague of mine, explaining that I would have to try to break down my research to explain it to a general audience. "How long is the presentation?" he asked. "I don't know, an hour?" I replied. Obviously, I hadn't read the website thoroughly, and I only wish there was a picture of the horror on my face when I discovered later that day that my presentation would have to be a measly 5 minutes.

It had been a while since my middle and high school days of watching science programs on TV, so I thought it wise to surround myself with examples of effective science communication in preparation. Heading back down the podcast rabbit hole, I started listening to The Infinite Monkey Cage on my commutes. It's a completely different flavor of show from Hidden Brain, in that it comes with a comedic twist and doesn't evoke the ASMR that Shankar's voice does. But it's still fun, and has a surprising amount of insight for a relatively non-serious podcast. (More recently, I've been enjoying a few more podcasts on my commute, including The Joy of x and My Favorite Theorem... and also Coffee Break French but that's probably less relevant to this post.) As the weeks wore on, I had to turn my podcast-listening efforts into a successful presentation.

Maybe I'm alone in thinking this, but in mathematics, I sense some low-level animosity against slide talks, and heaven help you if your slides are anything but a Beamer presentation. So imagine the panic when, for our Postdoc Spotlight presentations, we were encouraged to use PowerPoint (*gasp*). It had been years since I had opened the devil's program, and I was honestly a bit scared, but in the end, I've come to the controversial opinion that PowerPoint is actually fantastic. Now, let me clarify. I'm not saying most PowerPoint presentations are fantastic - that certainly isn't the case. But actually, I found that it was extremely well suited to the type of talk I was giving: clear but fast-paced, with wordless slides. (I haven't yet tried out PowerPoint for a research presentation, but maybe one day soon I'll make the jump.)

PowerPoint aside, there were two things which were important to me in preparing my talk. The first was that it legitimately had to be about my own research, as opposed to being purely expository. The second was that I had to present it with a certain level of integrity. Of course I would have to sweep some details under the rug, but I really didn't want to misconstrue what I was doing. I realized pretty quickly that the story I wanted to tell had two major threads, and I struggled to figure out how to tie them together. Throughout the process, I felt like I could produce an amazing 15-minute presentation with both of these threads properly treated, but that the 5-minute version always felt like a two-headed monster. The word "impossible" was thrown around at some point when I mentioned to a colleague what I was attempting to do, and for a while, I really believed it was an impossible task. As I cut out slides, the story didn't feel as coherent. As I rearranged the slides, it seemed like there was no solution. In a really early draft, I even had a bunch of slides which were overtly philosophical, attempting to answer the dreaded question of why pure mathematics is useful at all. It legitimately wasn't until the final version that I felt like I had produced a cohesive and compact story which fit in the time constraints.

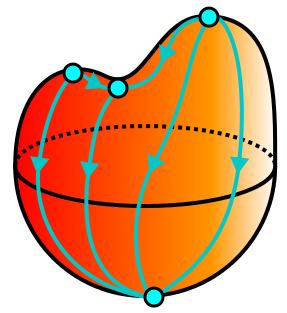

There were a number of things I learned from the process, and a lot of them can be phrased pretty generically (for example, distilling a message for a lay audience is actually helpful in understanding the big picture of one's own research). But I want to share a somewhat surprising one, which is that artistic direction is very important to me. I spent a lot of time designing my slides, and in the end, it's one of the aspects of my presentation that I'm most proud of. As a consequence, I've found myself really caring about artistry in my academic life, including not just the design of mathematical figures in lecture notes and research articles, but also the design of my website and this blog.

With all that out of the way, here is my presentation:

If you want to see the slides (not all of them appear in the video), click here.

For me, I feel this is the beginning of a journey. A journey about science communication which I'd like to complement my academic life. This blog is intended in many ways to be a realization of this journey.

Comments

Post a Comment