Physics for a Mathematician 02 - Witten's Supersymmetry and Morse Theory

We begin with Witten's Supersymmetry and Morse Theory (1982), which I had heard was a decent starting point for understanding the connections between physics and mathematics. The trouble with starting here, I have found, is a somewhat foundational problem:

The goal of this series is to delve into understanding physics for the eventual purpose of application in mathematics.

For Witten's paper, you have to know the physics already to truly understand the motivation.

That's not to say that there is not good mathematics in the paper, but rather that the physical arguments used come out of left field, which is a mixed blessing for me. On the one hand, I certainly don't understand every aspect of what Witten writes. On the other, it provides some direction for my foray into physics, since I have a better sense of what I need to learn. What I aim to do in this blog post is to describe (some subset of) the mathematics that Witten discusses, and to attempt to say something about some of the underlying physical principles. This last bit is particularly nontrivial: it's a main reason why this post has taken so darn long to write.

First, a few caveats:

Because the original post became too long as I was writing it, I decided to split it up into multiple parts, which will be posted over the next few days. This post will serve as a central hub, from which you can reach all of the other posts as you desire.

Links to the posts in this series:

First, a few caveats:

- This series of posts only works towards Sections 1 and 2 of Witten's paper, which I'll admit is as much as I read. Furthermore, with respect to Section 2, I'm only going to talk about the non-degenerate situation, since I don't think it's useful to worry about more technical details when my focus is on understanding the physics.

- Even when I discuss the physics, I'm going to be a bit cavalier in avoiding path integrals for now, mostly because I'm not so comfortable with them. Instead, I will be trying to state the part of the story which I understand, which at times is more heuristic than anything. I would appreciate any comments, fixing errors in my understanding or providing an extra part of the picture. Although I spent time trying to make the presentation look nice, please feel free to be skeptical, as I do not want to feign any sort of expertise.

- This series, Physics for Mathematician, is likely in general to be light on proofs. That is certainly the case here.

- I hope that some of these posts will be readable for first- or second-year graduate students in math (and maybe also physics?). I have done what I can to assume little prerequisite knowledge, though perhaps more strictly in some sections over others.

Because the original post became too long as I was writing it, I decided to split it up into multiple parts, which will be posted over the next few days. This post will serve as a central hub, from which you can reach all of the other posts as you desire.

Links to the posts in this series:

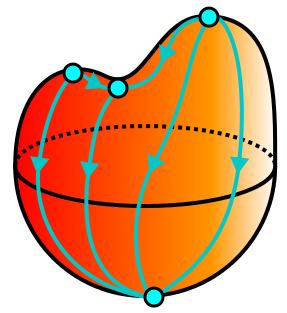

- Part I - The Morse-Smale-Witten Complex

- In this part, we describe the basics of Morse theory and give a definition of the Morse-Smale-Witten complex.

- Part II - Personal Bias vs History

- In this short post, I make a confession about my ignorance of the physics literature throughout graduate school.

- Part III - Physics Background

- In this post, we describe the basics of quantum mechanics from the perspective of the Schrödinger equation, including tunneling phenomena. We also describe the basic ideas of supersymmetry.

- Part IV - Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics From a Morse Function

- In this post, we discuss Witten's construction of the Morse-Smale-Witten complex from a supersymmetric quantum mechanical system coming from a Morse function

Comments

Post a Comment